A Collective Fever Dream

Thesis Performance and Digital Installation

A Collective Fever Dream

Thesis Performance and Digital Installation

While this page will function fine on mobile devices,

it is best viewed on a computer or a tablet in landscape mode.

You cannot be cared for by those who require you for profit.

Yet we trust that by giving our academic institutions our youth, our labor, and our money, they will in return give us the opportunities we require to grow and succeed as professionals and as people. And the statistics suggest that they do: according to one 2019 study, college graduates in the United States still earn, on average, $30,000 more than non-graduates. This is good for universities; it makes them a necessity. A college education is not so different from water or heat or electricity or even internet access: you can survive without it (many do), but not comfortably. And so — like many providers of utilities — universities enjoy an effective monopoly on that aspect of comfortable survival.

A monopoly benefits a few at the expense of many. However, in order to survive, a monopoly must convince its suffering majority that they are simultaneously benefitting from the arrangement, and that there is no viable alternative to it. This is easy to do in normal times, when the world behaves predictably and we as individuals are kept so occupied by the realities of adult life — work, family, friends, finances, education, personal betterment, unfettered corporate capitalism — that there is simply no room to consider the how and why.

But these are not normal times.

This is the foundation my thesis is built upon.

But before we can discuss it further, I should explain

what brought us here

Near the end of the Spring 2019 semester, I began work on what I planned to be my thesis exhibition. I was coming off an Advancement to Candidacy (ATC) project which had begun as a critique of academic art as a whole and had ended as a pointed critique of San José State’s program in particular. While this narrow focus proved effective for an audience mostly limited to faculty and peers, giving my thesis a broader scope would make it something I could more easily take with me into my professional career. Now that I was formally an institutional critic, I needed to expand my understanding of what qualified as an “institution.”

Earlier in the semester, shortly before debuting my advancement project, the romantic relationship in which I was involved abruptly fell apart. I came to understand some time later that — as is so often the case with these things — extenuating circumstances had likely led to the collapse. But in the moment the blame was placed squarely upon an old photographic print. During one of our many conversations about the autobiographical nature of my work, I had explained that this print remained on display in my personal space because of the technical achievement it represented. Unfortunately, it became clear too late that we had in fact not reached a mutual understanding.

The offending image: a gelatin-silver print made in a film enlarger from a digital image printed in negative on an overhead transparency with a Xerox photocopier, a process which I was originally told would not work, and so became determined to make work.

In response to this experience, I decided to create an installation around the offending photograph. My goal was to explore the complexity of assigning broad personal meaning to a single image, but I also hoped to address the perceived and actual responsibility of an individual to shield others from one’s own past. I wanted to challenge the viewer to consider their relationship with images — both their own but also those which belong to others. Should a person be expected to curate their own past for their partner’s comfort? Would their partner do the same for them? Does the answer change when the offending piece(s) are part of a person’s art practice?

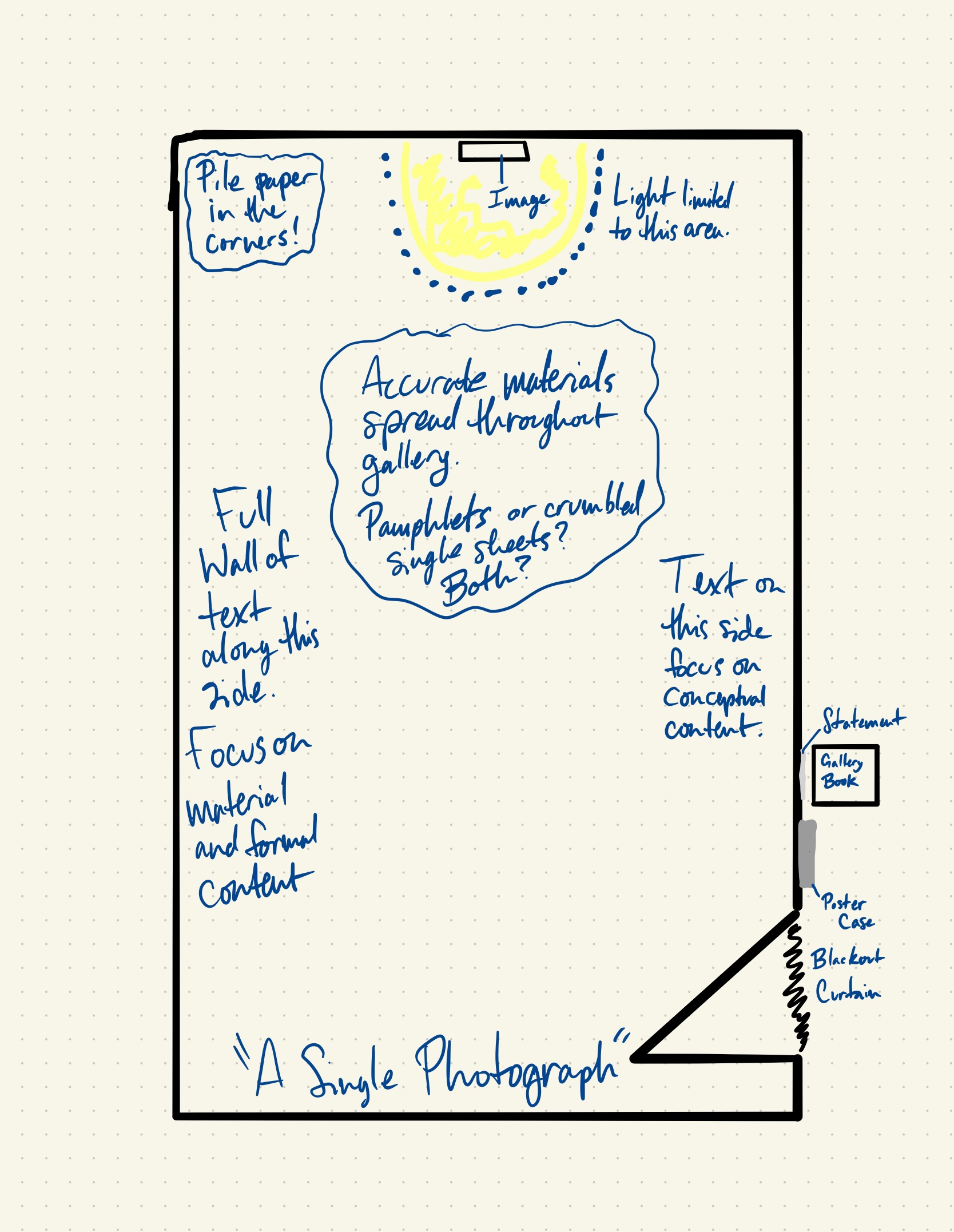

I planned to create a space which physically represented the complexity of meaning in a photograph: a room built around a single image, which contained all the information necessary to understand the print on the wall and why the show existed, but which would require the viewer to actively seek out information beyond the easy and obvious. I also imagined this process would be both enlightening and cathartic for me; a means of understanding a troubling situation and of understanding how others — particularly non-photographers — understood and interacted with my medium.

It was around this time that the title A Collective Fever Dream also came to be. Above the window in the door to our graduate studios hangs a wood plaque that reads “John Pickelle Gallery,” and the window itself had been turned into a space for displaying small pieces of art. However, when we began asking around, no one seemed to know who Mr. Pickelle was or why he had a “gallery” named after him. None of the faculty remembered any graduates or colleagues by that name, and it seemed as if the gallery had always been there.

The final concept sketch of my original thesis show. I was beginning production on materials for it when COVID-19 closed the SJSU campus and indefinitely postponed our round of thesis shows.

The John Pickelle Gallery, located in the SJSU Industrial Studies Building (left; featuring Sentimentality; or Unimportant Object #200108), and John Pickelle's presumed thesis, located in the thesis cabinet in the SJSU Art Building.

My fellow grad Alana Rios and I eventually stumbled across a thesis by one John Pickelle while researching in preparation for writing our own. The 2010 project was untitled, and contained only ten or so abstracted nude portraits and a handful of vague sentences for an artist statement. An attempt was also made to find and reach Mr. Pickelle through social media, to no avail. Following this, another grad jokingly suggested that perhaps John Pickelle had never in fact existed, and was instead some sort of “collective fever dream” shared by SJSU art graduates. This idea was so amusing that I wrote the phrase down in Sharpie on a loose piece of paper and hung it outside of my studio.

Eventually the title found its way into my thesis and I began planning my installation, but in late February 2020 campus was forced to close as COVID-19 swept through Santa Clara County. By the end of March the semester — and our thesis projects — had been suspended indefinitely.

It would be nearly eight months before my thesis had a solid deadline.

This delay, and the university’s actions during that time, are responsible for

the final form of this thesis

No one — no student, nor professor, nor university administrator — could have been fully prepared for the upheaval an uncontrolled global pandemic might inflict upon a university and those within it. However, it is generally understood that one major reason we have administrators is so that someone, somewhere, is considering possible scenarios where extra administrative guidance might be necessary, creating plans for addressing those scenarios, and leading the charge when such plans are implemented. A disaster, then, becomes an opportunity to test the soundness of those administrative plans, so that the university can continue to effectively serve the students who form and fund the institution.

In more ways than not, San José State University and its Art & Art History Department failed this test.

On March 9th, university president Mary A. Papazian announced that in-person classes would be suspended for two weeks in preparation for the university to “transition from in-person instruction to ‘distributed’ or ‘fully online’ instruction” in partial response to the first death linked to COVID-19 recorded in the county. During that time, campus and most of its facilities remained open; however, by March 12th, the situation had become dire enough for the university to order all instruction to move online. Campus and facilities closed shortly thereafter, thesis shows were cancelled without notification, and access to graduate studios was revoked without opportunity to gather personal belongings.

In hindsight, this sweeping response to the rapidly evolving situation was a wise reaction to the first wave of an illness that hit the city of San José and its surrounding county particularly hard. However, once the school had been shut down, there seemed to be little incentive for the department and university administrators to act quickly (or at all). In April, graduate students were finally offered three options to graduate: turn in all materials by the original deadlines in May — including a digital presentation of your thesis work — and graduate on time; delay graduation until August, using that time to develop a digital presentation of your thesis work; or delay graduation until the end of the Fall 2020 semester and hope that the student galleries reopened.

The SJSU MFA thesis guidelines are lacking to begin with. Last updated more than a decade ago, the three-page document suggests that the required book is not itself intended to be an actual thesis so much as formal documentation of the accompanying gallery installation. There is little in the way of additional guidelines for the installations themselves other than the expectation that they will take place in the student galleries during the allotted week. While this system works well enough under normal circumstances, in a situation where physical thesis shows become unrealistic or impossible — say, during a pandemic of society-disrupting proportions — these guidelines become effectively unusable. As we students have repeatedly attempted to make clear over the past eight months, if there is no show to document, there can be no document of a show. It would seem sensible, then, to adjust expectations and communicate clear, concrete guidelines for those of us unable to meet the standing expectations. This never happened.

An open letter, written by me and co-signed by the other two members of my original graduating photography MFA class, sent to the Department Chair and Graduate Coordinator seeking clarification on how we would be expected to complete our degrees. We had recieved zero guidance from the department at that time, and would not recieve a concrete plan for nearly another month.

I live nearly one hundred miles from campus, in the nearest affordable rental market I could find. I spent early every week for three years commuting by some combination of car, bike, and train to one of the most expensive metropolitan areas in the world, where I would rely on the kindness of friends and family to provide me with a place to sleep in the surrounding Bay Area until the weekend, when I would return to my apartment and part time job until the next week. And at the California State University with the shocking distinction of having the largest population of unhoused students — as well as a documented history of failing to effectively correct that distinction — I realize am one of the lucky ones.

Perhaps it should be no surprise that an institution so unable to guarantee the safety and well-being of its own students would ultimately be equally incapable of finding a way for those of us who completed our coursework to graduate on time. Students are fleeting in the eyes of a university, despite being the institution’s means to generate profit and prestige. When this is all over, this graduating class will be gone and replaced by new bodies and minds.

The earliest solution suggested was for students to simply move their graduation dates back another semester. Explanations as to why this was not a realistic option for many were met with frustration and dismissal. Inspite of these realities and due to inaction on the university's part, delay was the option a number of us were ultimately forced into.

While the university requires us to exist, we as individuals are inconsequential.

We are ultimately expendable.

So,

It would be easy to chalk this all up to the stereotype of art school being a place without structure or decorum, but SJSU is not an art school. This is a state school with an art program, and like most California State Universities, SJSU places a great deal of emphasis on their structures and paperwork and pyramid-shaped programs. The MFA thesis projects, though, have long been followed by a specter of insignificance — a suspicion reenforced in part by the oft-grumbled complaint from full-time and tenured faculty that they do not get paid extra to serve on graduate committees (one would think that a retirement program, health benefits, job security, union protection, and permanent access to funding and facilities that most graduate students will never receive would be compensation enough). This on its own should be a loud enough alarm-bell to warrant change.

But what if the thesis books were significant enough on their own? What if they were made easily and readily available to both the student body and the general public? The thesis shows are transient and, as this year has shown us, far too fragile to base a terminal degree around. The thesis books, however, are permanent. John Pickelle the Artist may have slipped from this place, but John Pickelle the Untitled Thesis, underwhelming as it may be, is a permanent part of this department. To relegate these books to mere documentation is misguided. As an institution based fundamentally in the belief that ideas ought to be maintained and dispersed, our program should end with an opportunity to do just that. Perhaps we've simply been doing this all backwards: the show should not make the book, the book should make the show.

I believe in this program; I believe that is capable of giving its students what they deserve. The problem is that you — the keepers of our institution — are so hung up on your process that you have forgotten to consider the full picture, and this year has rendered that process irrelevant. So now will you wait until the offended parties are gone and leave this all as it is, hoping — though you know better — that it will never be challenged again? Or will you challenge it yourselves, and finally build something meaningful out of what you now know was always on the verge of collapse?

I know from experience that there is a correct answer.

Jump to project:

A Collective Fever DreamThesis

DisposalPhotography

I've Never Been So Sure Of AnythingInstallation

godless children | holy objectsInstallation

No ThanksPhotobook

The Quiet CapitolPhotography

Finished FoodPhotography